the heritagization of the emigration from China

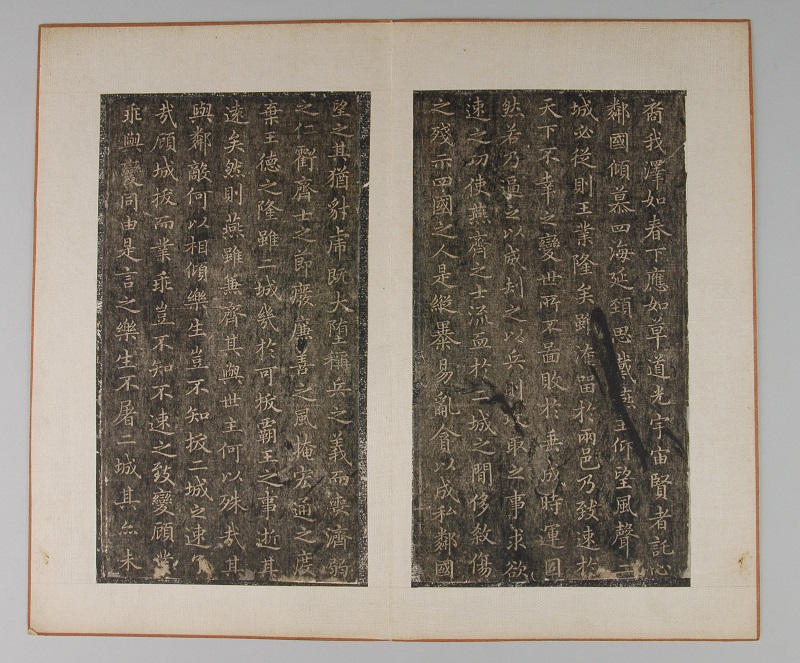

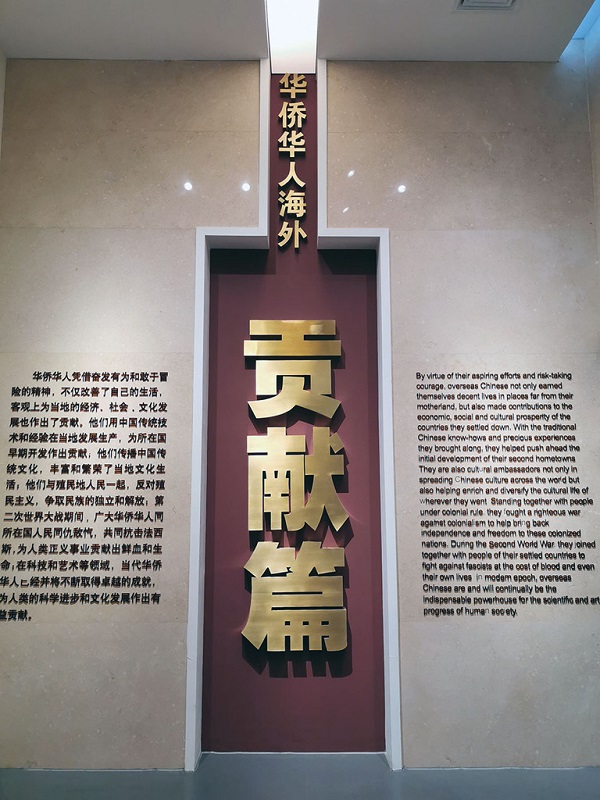

img. Part of the exhibition at the Overseas Chinese Museum of China, Beijing, source: http://www.7782tour.com/museum/27.html.

blog authored by dr. Martina Bofulin, Slovenian Migration Institute, Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

After the implementation of the reforms in the 1980s the Chinese state started to embrace a more diverse understanding of heritage. After the adoption of the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Convention in 2003, China experienced the so-called “heritage boom” that also included the new stance towards the legacies of emigration from China. For a long time considered to be traitors and agents of imperialism, Chinese emigrants, or Overseas Chinese as they are most often called, turned from ideologically suspicious to patriotic with their material and immaterial legacies being celebrated through museums, rituals, and monuments.

According to some estimates, there were at least 30 such museums across China, including major metropolises (Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou) as well as smaller places with strong emigration in Fujian, Zhejiang, Guangdong and even Yunnan and Heilongjiang provinces (Wang 2019). Among these, the flagship project is the National Overseas Chinese History Museum of China in Beijing officially inaugurated in 2014. As Wang Cangbai (2019) observes, these museums may differ in style and size but are very much alike in their monolithic patriotic discourse. This discourse emphasizes the contribution of the Overseas Chinese to China’s revolution (especially their contribution to the struggle against Japanese aggression) as well as subsequent modernization. Museums thus construct the Overseas Chinese as a highly unified “patriotic subject” who had suffered as a victim of Western colonialism and imperialism (Wang 2019).

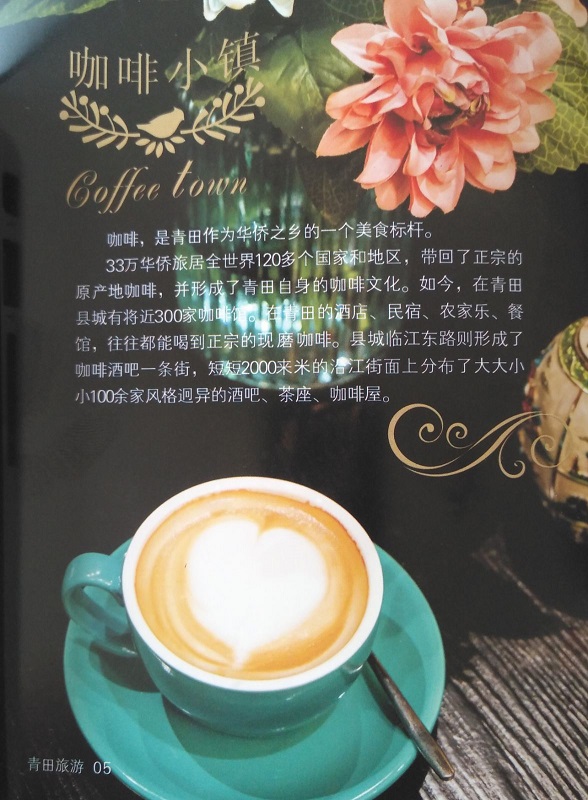

While on the national level the heritagization of Chinese emigration is highly ideological and does not depart in any way from the prescribed forms of the Chinese state’s metanarrative of the great revival of Chinese civilization under the CCP Chinese Communist Party, the heritagization at the local level pursues many more complex aims and gives local authorities more creativity for turning local practices and legacies into heritage. At the local level, the heritagization is much less ideological as it is practical – the main aims are local development through tourism, urban development as well as social cohesion, and successful town branding. But as the case of Qingtian county, a small “hometown of Overseas Chinese” in the southern Zhejiang province reveals, the migration legacies are mostly intangible practices that must be somehow made more palpable and material. In Qingtian, many resources are invested in creating an environment that reflects the century-long connection to Europe through migration. These legacies materialize in the local “European style” projects, including newly built monuments and buildings, as well as the celebration of particular consumption practices (e.g. coffee houses, wine drinking).

PAGODE – Europeana China is co-financed by the Connecting Europe Facility Programme of the European Union, under GA n. INEA/CEF/ICT/A2019/1931839