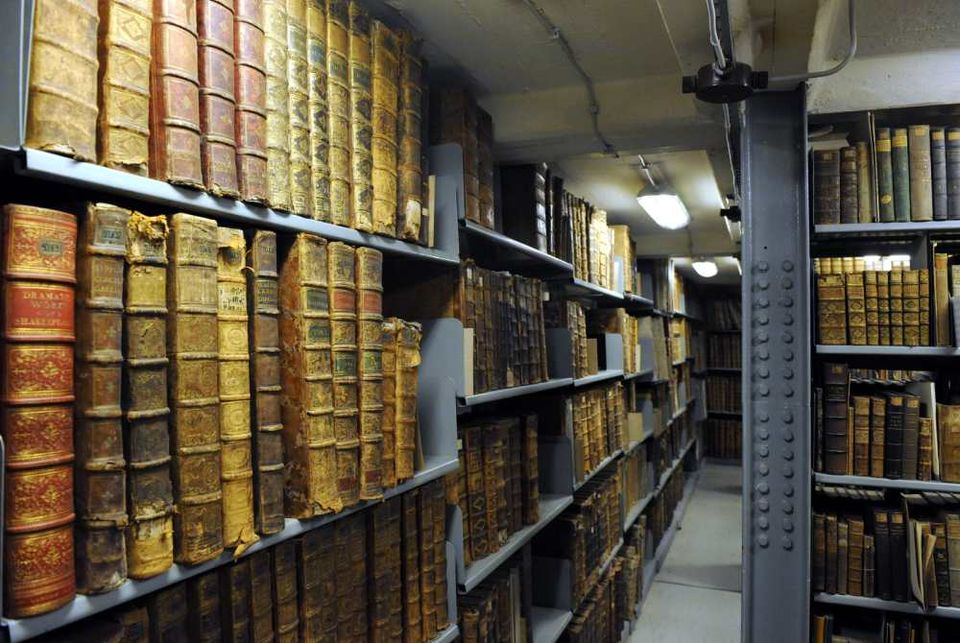

img. OSZK, Országos Széchényi Könyvtár, Hungary

Recently, an article by prof. Fred Truyen (KU Leuven, and Photoconsortium’s president) appeared on his Digital Culture blog, providing interesting considerations on the relationship between ICT and cultural heritage, that started since a long time and is now kind-of revitalized in the trending concept of “digital transformation” of the sector.

Arguing that “the ICT tools we should be looking at are not only the digitization, distribution, and visualization tools. It should include the participatory platforms that allow people to engage with the contents, to start commenting, selecting, curation, and co-creating stories.”, prof. Truyen summarizes the importance of an inclusive approach which, starting from offering access to relevant content and using the most appropriate technology, allows for a real change in the role and actions of cultural institutions.

Successful examples, particularly in the domain of education (such as the Fifties in Europe MOOC or the resources made available for teachers and students in the Europeana Education environment), showcase the immense potential of digital cultural heritage available online. Cultural Heritage Institutions are called to embrace the change, that is a very deep change, as Fred points out: “it is generally accepted that “Digital Transformation” – or the implementation of impactful ICT infrastructures – implies rethinking the core business processes and organizational workflows. This is what is happening today in the Cultural Heritage / GLAM sector. People look beyond the digital catalog or website portal to understand they need a coherent “digital strategy” to make sure their business processes and services are based on their information exchange systems.”

The effort of creating a successuful digital transformation experience of cultural heritage and cultural heritage institutions is a indeed highly complex task: while ICT tools are universally acknowledged as the “enabling element” of this recipe, as the yeast in a cake, it is clear that open access content cannot be the only other ingredient, as open access content is not user-engaging or meaningful per se. A multidisciplinary effort of curation is needed, both on the metadata side – by offering rich and relevant information that allows for the content of interest to be retrieved and interlinked, and on the storytelling side – by helping users associate interesting meanings to the content itself.

While the role of the human factor is particularly evident for the generation of good storytelling, it is also crucial on the side of information (to be) attached to digital objects. Nowadays AI and NLP techniques are appropriately cheered for enabling smoother automated metadata enrichment and interlinking: but to be effective and reliable they must be based on a structured semantic background, because the algorhitms are as much intelligent as we teach them to be; and for this reason highly specialized expertise and domain knowledge is needed in order to identify the descriptive keywords depicting a particular digital heritage object.

This is the case of project PAGODE – Europeana China that is thematically focused on Chinese heritage preserved in Europe and for which expert sinologists are working to define structured scientifical knowledge and guidelines on what can be considered as Chinese CH in Europe; on the typology of “objects” representing this heritage (tangible, intangible, natural e.g. landscapes) and finally on detailed speficiations for the metadata. The outcomes of this curation effort will improve the way (digital) cultural heritage relating to China is published, retrieved, interlinked, and finally reused via online repositories such as Europeana.