The 19th century – age of industrialization, immigration and democratization – thoroughly changed the way people lived, including patterns of leisure and recreation. Overall, during the early decades of the Industrial Revolution, popular leisure traditions declined substantially: in middle and high class families, the new working context and business ethics reshaped free time activities toward respectable domestic pastimes – such as reading or playing the piano – demonstrating an aim for personal improvement and family cohesion.

Workers had less time and means for play, and suffered the consequences of governmental attempts to limit ‘inappropriate’ forms of amusement, such as playing cards or betting on animal contests. Drinking, nevertheless, remained an important pastime and bars sprouted throughout working-class neighborhoods. As for any other activity, the main criterion was inexpensiveness: attending cheap concerts or circus shows, could at least for a few hours relieve the laborers’ minds from gritty everyday routine.

In the last quarter of the century, however, initiatives to further the working and living conditions of laborers bore fruits, the unions obtaining a rise of wages, the reduction of the workweek and the introduction of vacation days and free weekends. In the same period, middle-class professionals loosened their work ethics, cumulatively generating an increase in work-free time and a more receptive climate towards leisure and play.

Under these circumstances, the late 19th century witnessed the birth of modern leisure. Team sports were all the new rage, with amateur, professional and school teams uniting players from different layers of society. Stadiums were built and visited by a community of supporters that was equally heterogeneous, and women started competing in sports such as tennis or croquet. While visits to local pubs continued to be a favorite pastime, interest in cultural activities – such as concerts or museum visits – grew as well; the entertainment industry – with its many music halls, theatres and cinemas – boomed, as did the popularity of cycling and other outdoor activities – strolls, boat rides and picnics. Some leisure pursuits had a substantial social component: engaging in a friendly bowling game, meeting in a bar to occupy the billiard table, or wow neighbors and friends by showing off the newest motorcycle or racing car.

Many such an off-time moment has been captured not by amateur photographers only, but by professionals as well; Gaston Paris, for instance – the only salaried photographer for the French weekly magazine Vu – carried out many photo reports documenting the 1930s’ favorite pastimes: from world exhibitions and prestigious sports events, to glamorous recitals and theater performances. Paris himself contributed to the leisure industry not only with this type of reportages, common to photographer-reporters of that era, but with his visual renditions of horror stories and melodramas featuring gangsters and vamps for Detective Magazine as well.

Next to individual pastimes, organized recreation too enjoyed a boost in early modern Europe: from the mid-19th century onwards, the so-called ‘public recreation movement’ encouraged the establishment and spread of institutionalized free time activities and facilities by governments and voluntary organisms, aiming for a positive social outcome. Next to focusing on the development of parks and playgrounds, this movement favored adult education to stimulate intellectual cultivation and continuing personal improvement. Public lectures were installed, municipal libraries were constructed and courses for adults were set up for fundamental education as well as for ‘self-fulfillment’. The latter category embraced all kinds of liberal programs, from arts and crafts to music, theatre, dance and literature. A wide range of short- and long-term course trajectories would henceforth enable everyone to uncover and practice his or her innate talents.

In early modern Europe, tourism evolved into a leisure industry that was no longer the exclusive privilege of the rich and famous, but came within reach of the middle and working class as well. In the early 19th century, journeys throughout Europe for health reasons and cultural education – necessary to enable mingling in high society circles – were already common practice among the middle class. But with transport innovations, the tourist industry boomed: in the mid-19th century, steamships and trains made traveling faster, cheaper and more comfortable, soon enabling short, ‘domestic’ visits to the coast and the countryside as well as international tours and travels to destinations as far away as the United States and New Zealand. Just after the turn of the century, the first national tourist offices opened their doors.

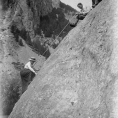

Pictures attesting to the tourists’ adventures, highlighting the extremity of the experience (climbing a mountain), the joy and carelessness of the occasion (splashing around in the sea with friends) or boasting exotic landscapes and people, were highly desirable souvenirs. Postcards adorned with such images lived their heydays in the 1890s, stimulated by the success of cards depicting the newly constructed Eiffel Tower. In the early 20th century, Kodak even launched a ‘Real Photo’ postcards-service, that allowed travelers to create postcards from their own pictures.